Mystery Babylon and the Lie of Becoming God

- Michelle Hayman

- Dec 18, 2025

- 30 min read

“And upon her forehead was a name written,

MYSTERY, BABYLON THE GREAT,

THE MOTHER OF HARLOTS

AND OF THE ABOMINATIONS OF THE EARTH.”

— Revelation 17:5

From humanity’s earliest history, questions of origin, life, and death have driven religious inquiry. The ancient mystery cults taught that such knowledge was not available to all, but only to those admitted through initiation into an exclusive spiritual system. They claimed that understanding life’s deepest truths required secrecy, discipline, and ritual participation.

These cults: devoted to figures such as Demeter, Isis, Mithras, Dionysus, and Cybele; centered on deities believed to have passed through suffering, death, and triumph. Their myths functioned as sacred models to be studied and ritually imitated. Through initiation and devotion, followers sought hidden knowledge, divine encounter, and assurance concerning death and the afterlife.

As M. J. Vermaseren documents in Cybele and Attis: The Myth and the Cult, the worship of the Great Mother developed over millennia and spread across the ancient world, eventually embedding itself deeply in Rome. Viewed through a biblical lens, the structure of these mystery religions; secret revelation, ritualized salvation, and devotion to a mother goddess; forms a historical framework for understanding the figure Revelation calls “Mystery Babylon.”

The Earth Goddess

In antiquity, throughout the Mediterranean world, the earth itself was worshipped as a goddess. While sky, sea, and underworld were assigned to male gods; Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades; the earth and its life-giving power belonged to a divine feminine figure. Known to the Greeks as Gaia, Rhea, Hera, or simply Mother Earth, this goddess was not revered for political authority but for her unique power to generate life. Prehistoric art already emphasized her fertility, portraying her with exaggerated female features to express abundance and creation.

Across Asia Minor, Crete, and early Greece, this deity appeared as the Great Mother, often worshipped in caves and on mountains. Over time she became both Mother of the Gods and Mother of humanity, since all life was believed to arise from the earth and return to it. Classical writers repeatedly affirmed this ancient belief: everything comes from the earth and ultimately returns to her. Thus the Earth Goddess ruled not only life and fertility, but death as well, encompassing both the visible world and the underworld in a perpetual cycle of birth, decay, and renewal.

Because this single feminine power was understood to operate under many names, she was invoked as Demeter, Persephone, Artemis, Aphrodite, or simply “the Great One.” Though her titles varied, she was always recognized as one divine feminine presence governing both this world and the next. This unity is vividly expressed centuries later in Apuleius, where the goddess Isis declares that she is worshipped under many names across nations, yet remains one and the same divine mother (in pagan religion).

Cybele, the Phrygian Great Mother of Asia Minor, belongs to this same family of goddesses. Hymns describe her as the Mother of the Gods, ruler of the cosmos, source of life for mortals and immortals alike, enthroned in majesty and drawn by lions. She is no gentle or idealized figure: Cybele is wild, ecstatic, attended by roaring beasts, delighting in drums, dance, and frenzy. This powerful earth goddess spread from Phrygia through Asia Minor, Greece, and the islands of the Aegean.

In 204 BC, Cybele was formally brought to Rome in the form of a sacred meteoric stone.

a black meteoric stone, believed to have fallen from heaven

There she became both a national goddess and the Mother of the Roman people, believed to protect the state and grant victory. Though officially controlled by the Roman Senate, her cult expanded across the empire. Temples were raised, priests and priestesses spread her rites throughout Europe, and her image; enthroned between lions, became a familiar sight from Asia to the West.

Despite regional adaptations, Cybele never lost her identity as the primordial Earth Goddess, sovereign over life and death. Associated with her was the youthful figure Attis (Osiris), whose myth centered on self-castration and rebirth, mirrored in the practices of her eunuch priests. Under the Roman Empire, Attis gained official recognition, and blood-baptism rituals such as the taurobolium spread widely, especially during the pagan revival of the late fourth century AD, when Cybele was increasingly viewed as a cosmic power.

Thus, beneath many names and rituals, one enduring figure remains: the Great Mother—ancient, universal, and intimately bound to humanity’s understanding of life, death, and renewal.

The Earth Mother as the “Mother of Harlots”

Scripture does not introduce Mystery Babylon as a political abstraction, but as a woman; a religious figure whose defining mark is motherhood. She is called “the Mother of Harlots and of the Abominations of the Earth” because she gives birth to false worship systems that spread across nations and generations. This image is not accidental. It directly confronts the ancient cult of the Earth Mother.

From the beginning, the Earth Goddess was revered as the source of all life, the womb from which gods, men, beasts, and plants emerged, and the grave to which all returned. She claimed authority over fertility, death, and rebirth; powers Scripture reserves for God alone. By presenting herself as the origin and end of life, the Earth Mother usurped divine sovereignty and redirected worship away from the Creator to creation itself.

This goddess did not demand exclusive devotion. Instead, she absorbed local deities, merged identities, and multiplied forms of worship under countless names; Demeter, Isis, Artemis, Cybele; while remaining essentially the same power. This is precisely why Scripture calls her a mother: she produced daughters. Each new cult, ritual, and mystery system carried her image forward, perpetuating spiritual adultery under new forms. What the Bible calls fornication, the ancient world called syncretism.

Revelation’s woman operates in the same manner. She is ancient, adorned, authoritative, and intoxicating. She does not destroy religion; she multiplies it. She unites nations not through truth, but through deception, mystery, and ritual. Her cup is filled with abominations; rites and doctrines that appear sacred yet defile those who drink. Like the Earth Mother, she promises life while dealing in death, claiming to mediate divine power while opposing the living God.

The Great Mother cults taught that salvation came through initiation, ritual imitation of dying and rising gods, ecstatic experience, and secret knowledge. Revelation exposes this system for what it is: idolatry dressed as motherhood, power without righteousness. The woman is not life-giving; she is drunk with the blood of the saints.

Thus, Mystery Babylon is not a new invention of the last days. She is the matured form of the ancient Earth Goddess; enthroned, glorified, and ruling over the religious imagination of the world. What once appeared as Mother Earth now stands unmasked by Scripture as the Mother of Harlots, the fountainhead of false religion opposed to the God of heaven.

Kubaba–Cybele: Mother of Gods, Men, Mountains, and Lions

From the earliest periods of human history, peoples around the Mediterranean worshipped a Mighty Mother; the Earth itself, believed to generate, sustain, and reclaim all life. She was understood as the fertile ground that receives seed, brings forth abundance, and finally receives all things back into her womb. Food, water, and life itself were attributed to her provision, and all other gods (initiates) were ultimately regarded as her offspring.

This Earth Goddess was consistently portrayed as excessively fertile. Early images emphasize heavy, abundant forms: full breasts, swollen belly, powerful hips and thighs. These features were not decorative but theological, proclaiming her as the source of conception and nourishment. Across Asia Minor and the Aegean world she appears kneeling, seated, or squatting, sometimes nursing a child or pressing milk from her breasts, reinforcing her identity as universal mother.

Because the earth was also perceived through the landscape itself, mountains were often seen as the body of the goddess. Peaks became her head, ridges her breasts, valleys her womb. As a result, mountains were worshipped as sacred, and caves and high places became her sanctuaries. The dead were buried in her depths, confirming her dominion over both life and death. She was thus revered as Mother of Gods, Mother of Men, and Queen of Heaven and the Underworld.

Rulers built fortified citadels on mountain summits and entrusted their protection to the Mountain Goddess. She became the divine guardian of cities and strongholds, enthroned above them. This is reflected in early monumental art, such as the Lion Gate at Mycenae and Cretan seal stones, where the goddess stands or sits between two lions, the ultimate symbols of power and fear. Though lions terrorized men and beasts alike, they were shown subdued at her side; guardians under her control, not equals.

Archaeological discoveries in Phrygia, Cybele’s homeland, confirm the great antiquity of this image. A terracotta figure from Çatalhöyük (c. 6000 BC) already shows the Goddess enthroned between two leopards, her heavy hands resting triumphantly on their heads. This early image became the prototype for millennia of religious art. Though later periods clothed her, crowned her with a mural crown, or refined her features, the essence never changed.

Across thousands of years, under many names, the same figure remains: the enthroned Earth Mother, ruler of mountains and beasts, giver of life, receiver of the dead, and sovereign over the cycle of birth, death, and renewal.

Hosea 13:7

“So I will be unto them as a lion: as a leopard by the way will I observe them.”

Early Forms of Worship and the Biblical Warning

From as early as 6000 BC, the worship of the Earth Mother already contained the core elements that would persist for millennia. Archaeological finds at Çatalhöyük show the Goddess enthroned, associated with birth, death, sexuality, and renewal. Scholars debate whether early images depict her giving birth to a divine son, receiving the dead back into her womb, or presiding over the death of a male consort. Whatever the precise interpretation, the meaning is consistent: life and death are mediated through the goddess, and access to renewal requires ritual proximity to her.

This pattern appears again and again across Asia Minor. The Great Mother is linked to mountains, stones, gates, thrones, lions, music, and ecstatic rites. Sacred spaces were carved directly into rock. Statues were placed in niches, doors, and gateways, appearing only at appointed festivals as divine “epiphanies.” The dead were buried in her domain, reinforcing her claim over both womb and grave. Over time, the cult absorbed foreign elements, including orgiastic practices and blood rituals, especially under Phrygian influence.

Kings and rulers aligned themselves with her worship. Fortresses, citadels, and tombs were placed under her protection. Lions flanked her images, pillars marked her sanctuaries, and high places became centers of devotion. What emerged was not merely reverence for nature, but a religious system that united sexuality, death, power, and mystery; mediated through stone, image, and ritual.

It is precisely this system that Scripture consistently condemns.

Yahweh does not forbid pillars, stones, and high places arbitrarily. He forbids them because they are the physical infrastructure of false worship:

“You shall tear down their altars, smash their sacred stones, and cut down their Asherah poles.”— Exodus 34:13

“You shall utterly destroy all the places where the nations you dispossess served their gods, on the high mountains and on the hills and under every green tree.”— Deuteronomy 12:2

* The “green tree” was not a generic reference to nature worship. In the cult of Cybele, the evergreen pine was sacred as the symbol of her consort Attis, whose death and rebirth were ritually commemorated through a cut pine tree. This tree represented Attis himself; castrated, slain, and renewed; making groves and evergreen trees central locations for her rites. The biblical command targets these specific cult sites, where fertility, death, and resurrection were ritually reenacted under sacred trees.

Pillars, carved stones, sacred gates, and enthroned images were not neutral art. They were the means by which humanity localized divine power, controlled access to the sacred, and replaced the living God with a system of ritual mediation. The Earth Mother cult taught that life, death, and renewal flowed from stone, mountain, and womb. Yahweh declared the opposite: life comes from Him alone.

The biblical command to destroy these objects is therefore not iconoclasm for its own sake, but a direct assault on a rival religious order; one that claimed ancient authority, universal motherhood, and control over the cycle of life and death. This same system, Scripture later reveals, matures into what Revelation calls Mystery Babylon.

Kubaba–Cybele: Her Name

Greek and Roman writers consistently believed that the Goddess with the lions originated in Asia Minor, naming Pessinus and Sardis as her principal centers. Her name appears in Greek sources in several forms; Kybele, Kybebe, Kybebē, Kybelis; all sharing the same root: Kube / Kuba. Even in antiquity, the meaning of this name was unclear, and many early explanations were speculative.

Some ancient and later writers associated her name with stone, noting that she was worshipped in the form of a sacred meteorite, especially at Pessinus. This led to theories connecting her name with cubic or sacred stones, though such etymologies remain uncertain. Others linked her worship to caves, chambers, and hollow vessels; features commonly associated with her cult; but these ideas explain her rituals more than the origin of her name.

More solid evidence comes from archaeology. A sixth-century BC inscribed jar fragment from Sardis, found near a lion altar, preserves the name Kuvava, which clearly corresponds to Kubaba, the name of a major goddess in Hittite sources. In Hittite and Neo-Hittite texts, Kubaba appears repeatedly as the Queen of Carchemish, where her temple was located. From Carchemish, her cult spread both northward into Cappadocia and southward into Syria.

Cuneiform records from Kültepe-Kanis (early second millennium BC) mention priests of Kubaba, and personal names such as Sili-Kubabat (“Kubaba is my protection”) appear in Assyrian trade documents. At Alalach and Ugarit, the goddess is invoked as “the Lady Kubaba, mistress of the land of Carchemish”, confirming her regional authority over centuries.

By the first millennium BC, the cult had moved westward. An inscription from Locri Epizephyrii in southern Italy (sixth century BC) refers to Kybele, written with the archaic Greek koppa, indicating that her worship arrived directly from Asia Minor, likely through Phocaean Greek colonies such as Marseilles and Velia.

After a period of obscurity following the collapse of the Hittite world around 1200 BC, the Goddess re-emerged in Phrygia, where she became known as Cybele, the national goddess of the Phrygians. From there she established her great sanctuary at Pessinus, before beginning her westward expansion that would eventually carry her cult to Greece and Rome.

Although the Phrygian language remains only partially understood, inscriptions from the seventh century BC onward repeatedly mention Attis, confirming that the goddess and her consort were already firmly linked in their homeland. Much of their original meaning remains obscure, but the continuity of names, places, and worship leaves no doubt that Kubaba and Cybele are the same ancient Mother Goddess, preserved under different tongues and titles.

The Cult in Asia Minor during Graeco-Roman Times

When Greek settlers migrated to Asia Minor and founded prosperous cities along the western coast after the Trojan War, they encountered the worship of the Great Mother everywhere. Deeply impressed by Phrygian religion, they readily adopted the Goddess and carried her cult with them as they founded colonies overseas. By the time Rome later absorbed Asia Minor, three cities stood out as especially important for Cybele’s cult: Troy, Pergamum, and Pessinus.

Troy held legendary significance because of the Palladium, the sacred image of Athena believed to protect the city. Roman writers; especially under Augustus; emphasized Rome’s Trojan origins, presenting Aeneas as their ancestor and linking Roman destiny to Phrygian sacred history. Although archaeological evidence shows that Cybele’s images at Troy largely date from the Hellenistic period, Roman political interest in Troy grew steadily. Roman leaders such as Sulla, Julius Caesar, and Augustus restored and honored the city, reinforcing its symbolic value.

Despite Troy’s prestige, Pergamum was the true gateway through which Cybele passed into Roman religion. Pergamum yields far richer evidence for her cult. On the great altar of Zeus (Jupiter) and Athena, built under Eumenes II, Cybele appears battling the Giants. The Attalid dynasty, whose name recalls Attis, cultivated close ties with Rome, and when Attalus III bequeathed his kingdom to Rome in 133 BC, religious and political interests aligned. Correspondence between the kings of Pergamum and priests of Cybele at Pessinus shows coordinated support for Rome, grounded in shared devotion to the Great Mother.

Pergamum contained a major Metroon near the city wall, from which the Goddess was transferred to Rome in 204 BC. Archaeological remains include a large seated statue of Cybele with a lion, strikingly similar to the later Roman statue on the Palatine. Additional Metroa and inscriptions show that the Attalid kings actively promoted her cult, and later Roman elites in Pergamum continued to display loyalty to Rome through devotion to Cybele.

Pessinus, though still poorly excavated, occupied a central role as Cybele’s sacred heartland. From there, Greek merchants and colonists spread her worship throughout the Mediterranean. She appears along the entire southern coast of Asia Minor, around the Black Sea, and as far as southern Russia and Thrace. Coins, reliefs, and statues testify to her presence in nearly every port, town, and village. Even in the Roman period, Phrygia never abandoned her worship.

The Goddess was known under many local names and epithets, usually tied to specific mountains or regions. Her imagery varied widely; enthroned, standing, flanked by lions, or paired with other deities such as Artemis, Apollo, or the moon god Men. In some monuments, Cybele and Artemis appear together; in others, she holds a lion while Artemis bears a hind. Inscriptions confirm extensive temple staffs, priestesses, musicians, and ritual specialists.

Numerous inscriptions illuminate daily cult life. At Colophon, decrees show Cybele (called Mother Antaia) honored alongside Zeus, Apollo, Athena, and Poseidon in civic planning and public ritual. At Cyme, records mention an archigallus overseeing cult property, with blessings for initiates and curses for outsiders. In Aphrodisias, a “House of Virgins” was dedicated to the Mother of the Mountains, complete with ritual musicians.

At Cyzicus, Cybele was worshipped under several titles, including Mater Dindymene. Archaeology confirms a major temple complex adorned with columns bearing statues of Attis, and inscriptions record priestly fees and ritual obligations. Reliefs show sacrifices involving cymbals, pipes, sacred trees, veiled priests, and blood offerings. One inscription recounts a miracle in which Cybele appeared in a dream to rescue a Roman soldier from captivity, reinforcing her reputation as a saving and protective goddess.

In an oracle from Apollo at Telmessos, preserved at Halicarnassus, advised the establishment of cults to Zeus Patroos, Apollo, the Moirai, the Mother of the Gods, and household spirits, confirming Cybele’s integration into the official religious framework of the Graeco-Roman world.

Across Asia Minor, Cybele was not a marginal deity but a pervasive religious authority, woven into politics, commerce, city planning, and personal devotion; long before her cult was formally enthroned in Rome.

The Beast Kingdoms and the Mother Religion

When the visions of Daniel and Revelation are read together, they reveal not only a succession of empires, but the continuity of a single religious system that moves through them. Although Scripture names these kingdoms symbolically, their locations and religious inheritance can be clearly traced.

Babylon (Daniel 2; 7); Mesopotamia

The source of mystery religion, fertility worship, sacred stones, and mother-goddess traditions.

The theological seedbed from which later systems grow.

Medo-Persia; Anatolia and the Near East

Asia Minor under Hittite and Persian control preserves and adapts the Mother Goddess (Kubaba).

The cult survives imperial transition without interruption.

Greece: Aegean world and western Asia Minor

Greek colonists absorb Cybele and spread her worship through cities such as Sardis, Pergamum, and Troy.

Syncretism intensifies as the Mother is merged with Artemis, Demeter, and other deities.

Rome: Italy and the Western Empire

Rome officially receives Cybele in 204 BC and enthrones her as Magna Mater.

What began in Babylon now sits at the center of imperial power.

Revelation exposes what Daniel only implies:the beast changes, but the woman remains.

She predates Rome, rides every empire, and finally sits enthroned in the last kingdom, revived Rome; fulfilling the vision of Mystery Babylon, the Mother of Harlots.

Bulls, Serpents, and the Blooded Cup

Inscriptions and reliefs from Asia Minor reveal that the cult of Cybele was not merely devotional but ritually charged, governed by strict purity laws. An inscription from the Metroon at Maeonia in Lydia (147–146 BC) requires ritual cleansing before entering the sanctuary. Contact with the dead, sexual intercourse, and bodily impurity demanded ablution and waiting periods. This was not moral repentance, but ritual purification, reinforcing the idea that access to the goddess required bodily regulation rather than righteousness.

Cybele’s sanctuaries were commonly located in caves, rock sites, or near sacred stones, reflecting her identity as an Earth and Mountain Goddess. Where formal temples existed, they were often placed beside major deities, especially Artemis, with whom Cybele was frequently merged. A striking relief, likely from Kula in Lydia, depicts Cybele enthroned between two lions; but here the imagery intensifies. The lions stand upon the heads of bulls, directly linking Cybele’s authority to the bull, the animal later sacrificed in the taurobolium and associated with her dying consort Attis.

Serpent imagery dominates the same relief. A winding serpent appears beside Cybele’s head, another climbs upward at her side, and two more decorate her throne. In ancient religion, the serpent symbolized earth power, renewal, and underworld knowledge. Together with the bull, it marks a theology of life drawn from death, fertility through blood, and rebirth through ritual.

Beside Cybele stands Demeter, holding a libation bowl over an altar and a sheaf of grain in her other hand. The libation bowl is critical: it represents the offering of liquid—wine or blood; to the gods, a ritual act meant to secure favor and life. In later Cybele worship, this symbolism culminates in the worshipper being washed in the blood of a bull, a counterfeit cleansing that Scripture later condemns. At the other side stands Nike, crowning the scene with victory, signaling triumph gained not through righteousness, but through ritual sacrifice.

Other reliefs repeat the same themes. At Smyrna, Cybele is enthroned as lions leap toward her, while below her throne repeated scenes of bull-versus-lion combat are carved—violence, dominance, and blood ritual frozen in stone. Musical ecstasy accompanies this imagery: cymbals, pipes, and frenzied dancers (maenads) surround her, dissolving restraint and reason in worship.

Smaller terracottas and coins spread these symbols into homes, graves, and marketplaces. Attis appears in countless forms; youthful, mournful, winged, dancing, or leaning against a column—always marked by vulnerability and death. His close association with the bull, and later with blood ritual, confirms his role as the sacrificial male, eternally subordinate to the Mother. Coins across Asia Minor display Cybele with lions and mural crown, and often pair her with Attis, proclaiming the divine couple as protectors of cities and guarantors of life.

Taken together, the bull, the serpent, and the libation bowl reveal the heart of this cult: life promised through blood, renewal through death, and divine favor mediated by ritual. It is this system; beautiful, ancient, and blood-soaked; that Scripture ultimately unmasks as an abomination.

In Revelation 17, this imagery is exposed and inverted: the woman holds not a sacred vessel but “a golden cup full of abominations and the filth of her fornication.” What appeared holy is revealed as corrupt; what claimed to give life is shown to intoxicate the nations. The cup has not changed; only its true contents are finally named by Scripture.

Cybele in Athens

Although Cybele originated in Asia Minor, her cult eventually took root in Athens, though not without resistance. Later Byzantine and Roman sources preserve a consistent tradition: an oriental priest of the Mother of the Gods (called a metragyrtes or gallus) arrived in Attica and initiated women into her mysteries. The Athenians rejected him as a dangerous religious innovator and killed him, after which a plague followed. An oracle then commanded the city to appease the offended deity. In response, Athens established a Metroon, consecrated to the Mother of the Gods, and turned it into the city’s official archive and law repository.

This detail is striking. The temple of the Asiatic Mother became the place where Athens stored its laws and public records, embedding her cult within the civic and political heart of the city. Although her more extreme oriental rites were never fully embraced, her identification with Rhea, Demeter, and Deo made her acceptable to Greek religion.

Evidence places the main Athenian Metroon in the Agora, near the Tholos, the seat of the city’s governing council. Archaeology confirms this location. Additional Metroa existed near the Ilissos River and at Agrai, while the port of Piraeus became a major center of her worship.

In the Agora, Cybele functioned as a state deity. In Piraeus, however, her cult began as a private foreign institution founded in the fourth century BC. Over time, the Athenians absorbed it, organizing it under local religious societies (orgeones). These groups appointed a priestess, not priests, and only much later; under Marcus Aurelius (AD 163/164); was a Roman state priest added, signaling imperial control of the cult.

Numerous reliefs and statues from Athens and Piraeus show Cybele enthroned between lions, sometimes alongside Hermes, Hecate, or Attis. One relief even names her Agdistis, presenting her standing before Attis in a gesture whose meaning remains obscure. Together, these images confirm that while Athens moderated the cult’s more violent expressions, it fully embraced the Mother Goddess as a protector of civic order, law, and stability.

Thus, even in the city famed for reason and philosophy, the Asiatic Mother found a permanent seat; quietly ruling from the archive of the laws themselves.

Cybele in the Rest of Greece

By the Roman period, the cult of Cybele had spread throughout mainland Greece, a fact confirmed by the careful travel accounts of Pausanias in the second century AD. His descriptions have proven so reliable that modern archaeology has repeatedly confirmed them, including the discovery of Metroa at Athens and Olympia. He also records temples or shrines of the Mother of the Gods at Akria, Thebes, Corinth, and elsewhere.

At Thebes, Cybele was worshipped privately in a shrine said to have been founded by the poet Pindar, who praised her under the name Dindymene. Night dances and songs in her honor involved Pan, nymphs, maenads, and Dionysian elements, revealing the ecstatic character of her worship. Across Greece, Cybele consistently appears alongside cave deities, music, and frenzy.

Material evidence confirms her widespread presence. Countless statues, reliefs, terracottas, and even silver objects show that she was venerated by both rich and poor. Many works were mass-produced in Athenian workshops and exported throughout Greece. In different cities, Cybele adapted to local religious structures, often merging with older earth cults. At Delphi, where Ge and Themis were already ancient figures, her introduction was smooth. On the Treasury of Siphnos, Cybele appears riding a lion-drawn chariot in the battle against the Giants.

At Eleusis, Cybele remained secondary to Demeter, yet writers such as Euripides ranked them closely. Some reliefs even place both goddesses side by side, each enthroned separately. In other regions, such as Lebadea and Thasos, Cybele appears enthroned as the principal goddess while Demeter and Persephone approach her in reverence; showing how her status could surpass local deities depending on place and period.

In healing centers like Epidaurus, where Asclepius ruled supreme, Cybele still received dedications prompted by dream revelations. A priest named Diogenes honored her with an altar alongside Asclepius, Apollo, Selene, and Hygieia, integrating her into the medical and dream-oracle tradition. Epidaurus also produced a hymn to the Mother with wild lions, echoing the ancient Homeric Hymn.

In cities such as Chalcis, Eretria, and Corinth, Cybele appears again; sometimes within sanctuaries of Isis, showing ongoing religious blending. At Corinth, Pausanias describes a temple of the Mother of the Gods positioned among shrines to Isis, Serapis, Helios, Ananke, and Aphrodite. A notable statue shows Cybele seated on a rock, her feet resting on a lion, flanked by symbols linked to Attis; the pine tree, syrinx, and shepherd’s crook; alongside a triple Hecate figure.

In the Peloponnese, Cybele’s ancient role as protector of cities endured. The famous Lion Gate at Mycenae already displays her heraldic imagery: two lions flanking a central pillar or tree, likely symbolizing the Goddess herself. In Roman times this role is formalized when Cybele wears the mural crown, identifying her with Tyche, the personified fortune of the city.

Although Attis appears less frequently in Greek contexts, representations of him do occur, mostly dating from the Roman period, confirming that while Greece moderated the cult, it never fully escaped its influence.

Cybele’s Advent in Rome (204 BC)

Cybele entered Rome at a moment of national crisis, during the final years of the Hannibalic War. Roman religion was already under strain, and foreign rites were spreading through the city. According to Livy, fear, superstition, and unregulated worship filled the Forum and Capitol, prompting the Senate to intervene and reassert control.

Rome had a long-standing policy of evocatio; formally transferring foreign gods into Roman territory, promising them greater honor in exchange for protection. In this context, Cybele’s arrival was not accidental but politically calculated. Several noble families claimed Trojan descent, tracing their lineage to Aeneas (Julius Caesar), and believed Rome’s fate, like Troy’s, depended on the favor of a powerful guardian deity.

The Sibylline Books declared that Italy could only be saved from a foreign invader if the Mother of Mount Ida was brought from Pessinus to Rome. After consulting the oracle at Delphi, Rome sent a distinguished delegation to King Attalus of Pergamum, Rome’s ally in Asia Minor. According to tradition, the Goddess was handed over in her most ancient form—a sacred meteoric stone, not an image shaped by human hands.

Roman poets embellished the event. Ovid describes the Goddess herself consenting to leave Asia, declaring Rome a worthy home. The stone was carried on a ship made of Idaean pine, tracing a symbolic route past Troy and Greek sacred sites before arriving at Ostia.

The Delphic oracle required that the Goddess be received by the best man in Rome, chosen as P. Cornelius Scipio Nasica, from the influential Scipio family. The Scipiones cultivated an aura of divine favor; Scipio Africanus was even rumored to have been conceived by a serpent, a claim he did not deny; an ominous detail given Cybele’s serpent symbolism.

When the ship carrying the sacred stone ran aground in the Tiber, a noblewoman named Claudia Quinta pulled it free with ease, a miracle interpreted as divine vindication of her purity. This event was celebrated for centuries in reliefs, coins, and cult memory, and further entrenched Cybele’s legitimacy in Rome.

On 6 April 204 BC, the stone was formally welcomed. Incense lined the streets. The Goddess was temporarily housed in the Temple of Victory on the Palatine Hill, and annual festivals; the Megalensia; were instituted. After ritual washing at the Almo River, the stone was carried in procession to the Palatine, the most ancient and symbolic of Rome’s hills, near the huts of Romulus, the city’s founder.

A permanent temple was prepared on this historic ground. Rome thus received not merely a foreign goddess, but its claimed Phrygian ancestry, enthroned on one of its sacred hills. Cybele had arrived; not as a peripheral deity, but at the heart of Roman identity, memory, and power.

The Seven Hills and the Palatine

In Revelation 17:9, the angel explains the mystery plainly: “The seven heads are seven mountains on which the woman sits.” From antiquity onward, Rome was universally known as the city of seven hills; a description used by Roman poets, historians, and coinage long before Christianity.

The traditional seven hills are:

Palatine

Capitoline

Aventine

Caelian

Esquiline

Viminal

Quirinal

The Palatine Hill is the most significant of all. It was believed to be the site of Romulus’s hut, the birthplace of Rome, and later became the seat of imperial palaces. When Cybele was brought to Rome in 204 BC, her sacred stone was installed on the Palatine, placing the Mother Goddess at the very heart of Roman identity and authority.

Thus, long before Revelation was written, a female religious figure was already enthroned on one of Rome’s seven hills. Revelation does not invent this imagery; it reveals its meaning. The woman who sits on seven hills is not symbolic geography alone, but a real, historically rooted religious power seated in Rome itself.

The Metroon on the Palatine

When Cybele arrived in Rome in 204 BC, she was welcomed as a war goddess (The Sixth Commandment states, “Thou shalt not kill” (Exodus 20:13, KJV), which Roman Catholic moral theology interprets through its Just War doctrine), meant to secure victory. Appropriately, her sacred stone was first housed in the Temple of Victory. Almost immediately, Rome began constructing a permanent temple for her on the Palatine Hill, the most ancient and symbolically charged of Rome’s seven hills. The temple was dedicated in 191 BC and became the official Metroon of the Great Mother.

Though repeatedly damaged by fires, the temple was consistently rebuilt by Rome’s elite. Metellus Numidicus restored it in the late second century BC, and later Augustus proudly claimed to have rebuilt it himself. His interest was not accidental: the Palatine was associated with Romulus, Troy, and Rome’s divine destiny. By restoring Cybele’s temple there, Augustus reinforced the idea that Rome’s origins; and protection; were bound to the Phrygian Mother.

Reliefs from the imperial period show how the Goddess was represented. Cybele herself was often not shown directly, but symbolized by an empty throne, a mural crown, a footstool, tambourines, and lions; a visual language of invisible but enthroned authority. This symbolic enthronement is striking in light of Revelation’s imagery of a woman who sits and reigns.

“How much she hath glorified herself, and lived deliciously, so much torment and sorrow give her: for she saith in her heart, I sit a queen, and am no widow, and shall see no sorrow.”

— Revelation 18:7 (KJV)

“With whom the kings of the earth have committed fornication, and the inhabitants of the earth have been made drunk with the wine of her fornication.”

— Revelation 17:2 (KJV)

Archaeological remains on the Palatine still show a seated Cybele flanked by lions, surrounding altars, and a nearby theatre used for the annual Megalensia festivals. The sanctuary remained active until the fifth century AD, long after Christianity was officially tolerated. Even then, the temple retained its sacred aura, as shown by the story of Serena, who was publicly rebuked for removing jewelry from the statue; an act still considered sacrilege.

Although the original black meteorite has never been found, excavations revealed that Attis was worshipped at the Palatine earlier than previously assumed. Terracotta figures from the first century BC show Attis as shepherd, musician, and sacrificial figure. This confirms that the Mother-and-son cult was already established at Rome’s heart before the imperial period, even if the later passion rites were formalized under Claudius.

Other Sacred Buildings of Cybele in Rome

Cybele’s presence in Rome was not limited to the Palatine. Her cult spread across several hills, embedding itself deeply into the city’s religious and social fabric.

On the Caelian Hill, opposite the Palatine, excavations revealed a large house belonging to Manius Publicius Hilarus, dating to the reign of Marcus Aurelius. Inscriptions identify this building as a meeting place (schola) for the dendrophori, the tree-bearers of Cybele. These officials were directly connected with the pine tree, the sacred symbol of Attis, which was ritually cut each year and carried in procession to the Palatine during the Attis passion rites. Inside the building were altars to Silvanus, god of the woodland, mosaics warding off the Evil Eye, wells for ritual use, and inscriptions invoking “the propitious gods”; clear evidence of organized mystery worship tied to Cybele and Attis.

A smaller Cybele shrine stood in the Forum Romanum, near the Via Sacra and the Arch of Titus. Depicted on reliefs and imperial coins, this round temple showed Cybele enthroned between lions. Though less important, its location along Rome’s sacred processional road demonstrates how thoroughly her cult permeated public space.

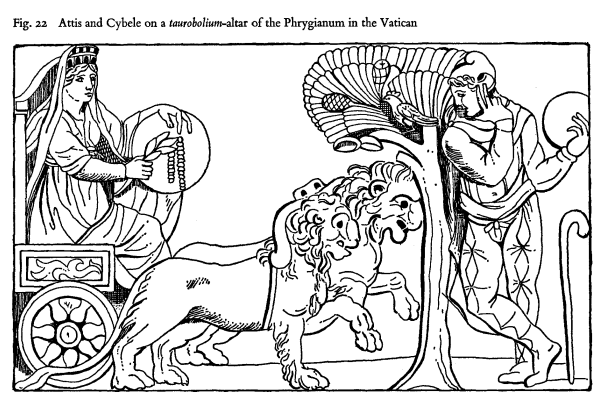

The Phrygianum on the Vatican Hill

Most significant of all was the sanctuary of Cybele and Attis on the Vatican Hill, across the Tiber, near the Circus of Caligula and Nero. Ancient sources call this complex the Phrygianum. Although the Vatican Obelisk was erected in St. Peter’s Square in 1586, the lion symbolism associated with its setting belongs to the 17th-century Baroque program (1656–1667), when Gian Lorenzo Bernini redesigned the piazza into a vast, theatrical sacred space. This development is especially striking in light of earlier archaeological discoveries: in 1609, numerous pagan altars were uncovered beneath and around what is now St Peter’s Basilica, indicating that an extensive pre-Christian sanctuary once occupied the same ground. Although never fully excavated, the wide distribution of these altars suggests a large ritual precinct, comparable to the Cybele sanctuary at Ostia. Rather than dismantling the ancient stone and its cultic associations, later builders preserved the monolith and, within a generation, framed it with symbolic beasts, visually reintegrating the pillar into a renewed sacred landscape. The sequence of dates is revealing: the stone was not cut down, but re-enthroned, and the beasts were placed around it.

Crucially, this Vatican sanctuary was the exclusive site in Rome for the taurobolium and criobolium; blood rites in which worshippers were cleansed or reborn through the sacrifice of a bull or ram (see the book of Daniel). Almost all known altars from this site commemorate such rituals. Most date from the fourth century AD, with a notable interruption that coincides closely with the construction of the first Constantinian basilica of St Peter. Archaeologists have long observed that building activity likely disrupted the pagan rites, even as the sacred space itself was never ritually cleared.

The imagery on these altars is consistent and revealing:

Pine trees (Attis)

Shepherd’s crook and pipes

Bull and ram heads (taurobolium / criobolium)

Libation vessels (patera, urceus)

Cymbals and castanets

Torches and augural staffs

One altar shows a bull and ram beneath a pine tree, with Attis’ instruments hanging from its branches. Another depicts Cybele riding past a pine tree in her lion chariot, while Attis stands beneath it as shepherd. Libation bowls repeatedly appear, emphasizing blood, pouring, and ritual offering as central to the cult.

Elite Participation and Religious Blending

The inscriptions reveal that Cybele’s Vatican cult was not marginal but supported by senators, city prefects, and high-ranking priests. These men often held multiple religious offices simultaneously; priests of Mithras, Isis, Liber/Bacchus, Hecate, Sol, and Cybele; demonstrating deliberate religious fusion at the highest levels of Roman society. Titles once reserved for state gods, such as custodes and conservatores, were applied to Cybele and Attis, effectively transferring the language of imperial protection to a mystery cult.

Several inscriptions explicitly connect bull sacrifice with both Mithraic bull-slaying and the taurobolium, showing how blood symbolism unified different cults. One rite even involved collecting the testicles of the sacrificed animals in a cernus, a ritual vessel also used in the mysteries of Demeter and Proserpina, further blending mother-goddess traditions.

Biblical Significance

Scripture repeatedly commands the destruction of high places, sacred trees, altars, and standing stones (Deut. 12:2–3; Exod. 34:13). Yet on the Vatican Hill, pagan altars, blood rites, sacred trees, and ritual vessels were not destroyed but eventually built over. The ground was reoccupied, not cleansed.

Revelation’s warning is therefore not abstract. A woman associated with blood, ritual, power, and ancient religion truly sat enthroned on Rome’s hills, and even when her temples fell silent, her stones remained.

“Mother of All That Exists”

Late pagan inscriptions and poems from Rome; especially those connected with the Vatican Phrygianum; present Cybele and Attis not as local deities, but as cosmic powers. In these texts, Cybele (Isis) is repeatedly identified with Rhea, the primordial Mother, and praised as the source of all life, nature, and death. Everything comes from her womb and ultimately returns to it. She is called the Mother of all that exists.

Attis (Osiris), her consort, is elevated alongside her. He is addressed as hypsistos (“Most High”) and described as the one who “spans all creation” and makes all things flourish. This language is not accidental. It belongs to the vocabulary of mystery religions, influenced by Stoic philosophy and borrowed terms familiar from Jewish synagogue usage, where “Most High” referred to God alone. In these inscriptions, that title is deliberately transferred to Attis.

Blood ritual stands at the center of this theology. Altars are repeatedly dedicated after initiation through the blood of a bull and a ram; the taurobolium and criobolium. These sacrifices are called symbols of salvation, promising renewal, rebirth, and the restoration of light after darkness. One poem explicitly states that after a long interval; twenty-eight years; darkness was driven away and light returned again through renewed sacrifice. This reflects a cyclical worldview: death gives life, blood brings salvation, and time endlessly renews itself.

Several inscriptions reveal that these rites were performed by Rome’s highest elites; senators, city prefects, and state priests; many of whom simultaneously served as priests of Mithras, Sol, Isis, Liber, and Hecate. The mystery cults were not rivals but allies. Their symbols overlap: bull sacrifice, light versus darkness, rebirth, and cosmic order. Attis’ blood is quietly aligned with Mithras’ bull-slaying, and both are treated as salvific acts.

One recurring theme is totality. Cybele is praised as ruling nature “from day to day,” Attis as sustaining creation, and together they are called omnipotent gods. This is not folk religion but a developed theological system offering universal salvation, guarded by initiates (mystai) and sealed in blood.

Biblical Contrast

Scripture consistently attributes these claims to God alone:

Creator of all things (Genesis 1; Isaiah 44:24)

Most High (El Elyon)

Giver of life and judge of death

Yet here, those divine titles are transferred to a Mother Goddess and her dying consort, whose salvation depends not on repentance or covenant, but on ritual blood and hidden knowledge. Revelation later unmasks this system, not as harmless symbolism, but as a counterfeit gospel; ancient, powerful, and clothed in religious language.

The “Mother of all” and the “Most High” Attis are not forgotten relics. They represent a worldview Scripture explicitly condemns: life from blood not appointed by God, salvation without truth, and divinity claimed by creation itself.

The Theft of Sacred Titles

Mystery religions deliberately borrowed the language of Scripture to claim legitimacy. Titles such as “Most High” (hypsistos), “omnipotent,” and “saviour” were not accidental poetic flourishes; they were theological claims. By applying these names to Cybele and Attis, the mysteries presented their gods as universal, eternal, and supreme; attributes the Bible reserves for God alone.

Daniel explicitly warns of this strategy. The final kingdom is described as one that “speaks great words against the Most High” (Daniel 7:25), not merely by open blasphemy, but by appropriation; claiming divine authority, titles, and functions that do not belong to it. When Attis is called hypsistos, the warning is fulfilled: the Most High is not denied, but replaced.

Revelation exposes the result. What appears clothed in sacred language is revealed as counterfeit power, ancient, seductive, and opposed to the truth; Mystery Babylon, not by accident, but by design.

The Goddess of the Circus Maximus

Cybele’s identity as Mother Earth naturally extended to death as well as life. What comes from her womb must return to it, and so she became not only a giver of life, but a guardian of the dead. This helps explain why, when Rome established her cult, her temple on the Palatine (Germalus) was deliberately positioned overlooking the Circus Maximus, a place long associated with funeral games, blood, and the transfer of life-force through ritual competition.

The veneration of bones and relics, ritual prostration before images, and the exaltation of a crowned “Queen of Heaven” have no foundation in apostolic Christianity. These acts mirror ancient goddess cults, not the worship taught by Christ and the apostles. Dressing such rites in Christian language; by renaming the figure “Mary”; does not alter their substance; it merely disguises idol worship in ecclesiastical form.

In ancient belief, games held for the dead; like those described in Homer and depicted in Etruscan tombs; were not mere entertainment. They were acts of magical nourishment, meant to strengthen the deceased and the earth itself through exertion, bloodshed, and victory. Under this logic, the Circus was placed under the protection of Cybele, the Goddess who ruled both fertility and death.

During the Megalensia festivals each April, Cybele’s statue was carried from her Palatine temple to the Circus. From there she presided over the races as patroness of the games. Over time, her presence became permanent. Artistic evidence; coins, mosaics, lamps, and sarcophagi; repeatedly depicts Cybele riding a lion on the spina (the central barrier of the Circus), near the great obelisk later moved by Augustus.

Across these representations, certain features remain constant:

Cybele wears the mural crown, symbol of city-rule

She rides or controls a leaping lion

She is positioned beside an obelisk (sacred stone)

The races circle the spina seven times

This is not incidental symbolism. A female deity enthroned among stones, blood, spectacle, and sevenfold circuits dominates Rome’s greatest public arena. Even as emperors changed, the image endured. Under Trajan, Antoninus Pius, and later emperors, Cybele’s presence at the Circus was reinforced through coinage and imperial iconography. She became inseparable from Roman identity, victory, and public life.

Questions That Must Be Asked

Why was a Mother Goddess, associated with blood, death, and rebirth, enthroned at the heart of Rome’s greatest public monument?

Why were sacred stones and obelisks, which Scripture commands to destroy, preserved, honored, and relocated rather than removed?

Why does the Vatican Hill, once the site of Cybele’s blood rituals (the Phrygianum), still display an obelisk at its center today?

If God commanded, “You shall utterly destroy their altars… and cut down their sacred trees” (Deut. 12:2–3), why were these cultic symbols absorbed and repurposed instead of abolished?

Revelation does not speak in abstractions. A woman enthroned amid power, blood, spectacle, and stones; sitting on Rome’s hills; was already visible centuries before John wrote. The question is not whether the imagery fits history, but why history fits the imagery so precisely.

“And I saw the woman drunken with the blood of the saints, and with the blood of the martyrs of Jesus…” Revelation 17:6

Revelation 17:9

“And here is the mind which hath wisdom. The seven heads are seven mountains, on which the woman sitteth.”

Very hypocritical considering the story of Jesus himself it a re-enactment of these very ancient stories you mentioned. It was a Roman consolidation of power through the story of Jesus and you have pledged your god given soveriegnty and soul to them under the guise of good. The most Satanic wolf hides in sheep's clothing. Romulus and Remus.