From Ekklesia to Empire: Chalcedon and the Monetization of Faith

- Michelle Hayman

- Jan 13

- 16 min read

The Council of Chalcedon stands as one of the most decisive moments in early Christian history, not because it invented doctrine, but because it formally drew boundaries around what the Church understood itself already to have received. The council did not see its task as creative or progressive; it understood itself as custodial. What was at stake was not innovation, but preservation; the guarding of the apostolic faith against distortion, corruption, and misuse.

Chalcedon is often remembered primarily for its Christological definition, clarifying that Christ is one person in two natures, fully divine and fully human, without confusion, change, division, or separation. Yet alongside this theological clarification, the council also issued disciplinary canons that reveal something equally important: how seriously the early Church regarded the integrity of ministry, authority, and grace itself. These canons show that right belief and right practice were inseparable. To confess Christ rightly while corrupting the means by which his life was mediated to the community was considered a contradiction.

One of the most striking of these canons addresses the buying and selling of ecclesiastical office. It states, without hesitation, that grace is unsaleable. Ordination, appointment, and authority are not commodities, and any attempt to attach money to them nullifies the act itself. A bishop who ordains for money forfeits his rank. The person who purchases ordination gains nothing from it and is removed from the position obtained. Even those who merely facilitate such transactions are condemned. The language is not mild, and it is not pragmatic. It is moral, theological, and absolute.

What is especially revealing is the assumption underlying this ruling. Ministry is not a career path, advancement is not transactional, and authority is not transferable by human negotiation. Grace proceeds from God alone, and when human systems attempt to monetize what is divine, they do not merely abuse the Church; they cease to act as the Church. The ekklesia, the called-out assembly, is not sustained by wealth, influence, or administration, but by fidelity to what has been given.

The council makes no allowance for cultural custom, financial necessity, or institutional convenience. It does not suggest reforming corrupt practices; it abolishes them outright. There is no argument that “everyone does it,” no appeal to stability, and no exemption for rank or office. Bishops are judged by the same standard as clerics, monks, and laypeople. Authority does not excuse corruption; it magnifies its seriousness.

This raises an unavoidable question for later centuries. If Chalcedon understood such practices to be incompatible with the faith it was defending, what does that say about systems that later normalized, regulated, or depended upon precisely what the council condemned? The canon does not expire, soften, or qualify itself with time. It assumes continuity; that what was unlawful then remains unlawful now.

To read Chalcedon honestly is to confront a vision of the Church that is far less flexible than modern Christianity often assumes. Doctrine is fixed, not evolving. Grace is given, not sold. Authority is accountable, not self-legitimating. And the Church exists as a people formed by truth and faithfulness, not as an institution sustained by transaction. Whether one agrees with Chalcedon or not, its voice is clear; and it speaks uncomfortably into the present.

The same council that condemned the buying and selling of ordination also addressed a related corruption: the gradual entanglement of the clergy with wealth, property, and worldly administration. The sacred synod records that it had come to its attention that some enrolled among the clergy were acting as hired managers of other people’s property for sordid gain, involving themselves in secular business, frequenting the houses of wealthy patrons, and neglecting the service of God. This is not framed as a marginal abuse, but as a distortion serious enough to require formal prohibition.

What is striking is the council’s clarity about incompatibility. Clerical ministry and the management of worldly wealth are treated as fundamentally opposed callings. The issue is not merely distraction or excess, but avarice itself. The council does not say that such behavior risks scandal or weakens witness; it says it violates the purpose of the clerical vocation. As a result, it decrees that no bishop, cleric, or monk may manage property or administer secular business, except in narrowly defined cases of unavoidable legal responsibility, such as the care of minors, or in explicitly ecclesiastical works of mercy like the support of orphans, widows, and those in genuine need. Even then, such involvement is framed as reluctant service under compulsion, not opportunity.

The logic here is consistent with the earlier condemnation of simony. If grace cannot be sold, then ministry cannot be leveraged. If ordination is not a commodity, then office cannot become a platform for financial influence. The council assumes that once clergy become administrators of wealth, the boundary between service and profit collapses. The result is not merely personal corruption, but a blurring of what the ekklesia is meant to be.

The same concern extends to monastic life. Chalcedon draws a sharp distinction between those who truly and sincerely live the monastic vocation and those who merely adopt its outward form while inserting themselves into ecclesiastical and civic affairs.

This is particularly revealing because it runs counter to later romanticized ideas of charismatic religious initiative. Chalcedon does not celebrate individual zeal unmoored from accountability. It insists that even ascetic devotion must remain ordered, local, and answerable, lest it become another form of self-assertion or economic exploitation.

Throughout these decrees, a single concern remains consistent: that the name of God not be blasphemed. For Chalcedon, blasphemy does not arise only from false doctrine, but from visible contradictions between confession and conduct. When clergy become managers, brokers, and power-holders; when monks become political actors; when ministry becomes a means of access or income; the faith itself is dishonored. This is why the council attaches real penalties to these transgressions. The issue is not personal holiness alone, but the integrity of the ekklesia as a people called out of the world, not reorganized to resemble it.

Read together with the condemnation of simony, these canons present a vision of the Church that is austere, restrained, and deliberately resistant to monetization. Authority is circumscribed, wealth is suspect, and religious roles are narrowly defined to prevent their absorption into social and economic systems. Chalcedon does not imagine the Church as an institution sustained by property, revenue, and administration, but as a community sustained by fidelity, prayer, and truth. That vision stands in sharp tension with much that would emerge in later centuries; not because the council failed to anticipate abuse, but because it anticipated it all too clearly.

This matters because it gives us a standard that predates medieval Catholicism, papal states, modern parishes, and contemporary financial defenses. It gives us a way to evaluate what came later without appealing to modern outrage or Protestant polemic. The council itself becomes the measuring rod.

The first major shift comes when the Church is legally permitted to accumulate property. In the fourth century, laws allowed people to leave estates to the Church by will. From that point, the Roman Church in particular began to acquire land, revenues, and long-term assets. At first these were justified as resources for charity and stability, but assets require administration, and administration requires power. Over time, what began as patrimony became political influence, and what began as stewardship became sovereignty.

By the early medieval period, the papacy was no longer only a spiritual authority. It was also a territorial ruler. Revenues no longer came only from offerings but from rents, taxes, monopolies, and state finance. Once that happened, the danger Chalcedon warned against was no longer hypothetical. Clergy were now administrators by necessity. Offices carried income. Influence carried access. The conditions for simony were built into the system itself.

Simony did not explode in the Middle Ages because people suddenly became worse. It exploded because spiritual office had become economically valuable. When a position brings land, revenue, or power, people will pay for it. Chalcedon’s judgment on this is devastatingly simple: if office is bought, it is void; if it is sold, the seller is disqualified. It does not matter how useful the institution is afterward. The act itself breaks communion.

This brings the issue directly into the present. Practices like Mass offerings and Mass cards are often defended with careful language. They are called donations, stipends, or freewill offerings, and it is insisted that no price is being charged for grace. Yet the social reality is harder to ignore. People routinely experience these practices as transactions: money is given, and a spiritual act is performed for a specific intention. Modern church law itself admits the danger by insisting that even the appearance of trafficking in spiritual things must be avoided.

From a Chalcedonian perspective, that admission is already an indictment. The council did not ask whether people meant well or whether funds were later used for good causes. It asked whether grace was being placed in a position where it could be perceived, experienced, or handled as a commodity. If it was, the practice was condemned.

This is why appeals to charity, however sincere, do not answer the deeper problem.

Chalcedon explicitly allows involvement with resources for the sake of the vulnerable. What it forbids is the transformation of ministry into administration and the normalization of wealth as a defining feature of religious life. When churches accumulate treasure while people sleep on the streets outside them, the contradiction is not merely moral; it is canonical. The council foresaw this exact defense and refused it in advance.

Does this mean Chalcedon “nullifies” the Church’s authority? Not in the sense that truth disappears or Christ ceases to be Christ. But it does mean that authority is conditional, not automatic. Chalcedon does not allow the Church to claim legitimacy simply because it is the Church. Authority depends on fidelity. When spiritual acts are monetized and offices become commodities, the council says that authority is forfeited, not merely compromised.

That is what makes Chalcedon so uncomfortable to read today. It does not flatter institutions. It does not excuse success. It does not equate continuity with faithfulness. It assumes that the Church can betray itself, and it legislates accordingly.

The uncomfortable conclusion is this: if later Christian systems normalized what Chalcedon explicitly condemned, then the problem is not merely abuse within the Church. The problem is a contradiction between what the Church once declared itself to be and what it later allowed itself to become. Chalcedon does not need modern critics to indict later corruption. It already did so, in advance.

Before drawing conclusions, it is worth laying out the historical record plainly. If the Church of Christ is the ekklesia; the called-out body of believers; then any institution claiming continuity with that Church must be measured against what it actually did, not merely what it professed. What follows is not polemic, but documentation: a list of the ways wealth, monetization, and power became embedded in the institutional church over time, in direct tension with the boundaries established at Chalcedon.

Large-scale land accumulation by the institutional church beginning in the 4th century through imperial grants, aristocratic donations, and inherited estates, creating permanent income streams from rents, agriculture, and later urban property.

The development of the Patrimony of Peter, where land and wealth were attached to ecclesiastical office rather than to the needs of the poor, turning spiritual authority into a mechanism for long-term asset control.

The rise of the Papal States, in which the bishop of Rome functioned as a territorial ruler, collecting taxes, tolls, and revenues indistinguishable from secular governments, despite Chalcedon’s prohibition against clergy engaging in worldly administration.

Simony: the buying and selling of church offices, benefices, and ecclesiastical influence, repeatedly condemned yet repeatedly practiced, directly violating Chalcedon’s ruling that grace is unsaleable and that bought ordinations confer no spiritual benefit.

The sale of bishoprics, abbeys, and benefices, where positions were treated as income-generating assets, often purchased by wealthy families and used to secure political power or family wealth.

The monetization of sacraments and spiritual acts, including payments associated with masses for the dead, indulgences, and blessings, creating the perception and experience of spiritual transactions despite formal denials.

The institutionalization of Mass stipends and Mass cards, where money is routinely linked to specific spiritual intentions, contradicting the Chalcedonian principle that spiritual acts must never resemble commerce.

The accumulation of treasure, gold, art, and luxury goods, including vast collections held while poverty persisted outside church doors, undermining claims that wealth exists solely for charity.

The operation of financial systems and investments, including banks, real estate portfolios, and modern asset management structures, placing clergy and church officials in precisely the role of worldly administrators Chalcedon forbade.

The transformation of ministry into a professional career path, with salaries, advancement structures, credentials, and institutional gatekeeping, replacing the apostolic model of service with bureaucratic hierarchy.

The selling of religious books, devotional items, sacramentals, and branded materials for profit, monetizing the name of Christ and the faith of believers rather than freely giving what was freely received.

The use of donation pressure, guilt, fear for the dead, or appeals to obligation to extract money from the faithful, particularly the vulnerable, in contradiction to the gospel’s insistence on voluntary giving without compulsion.

The defense of wealth accumulation by appeals to charity, while maintaining systems that perpetuate inequality, clerical privilege, and institutional self-preservation rather than radical care for the poor.

The claim of authority based on institutional continuity, even when practices directly contradict ecumenical councils and apostolic teaching, replacing fidelity with self-legitimization.

The conclusion that follows from Chalcedon is not complicated, but it is uncomfortable. The Church of Christ is the ekklesia; the called-out body of believers. It is a people formed by faith, obedience, and shared life in Christ, not an institution sustained by wealth, property, or commercial activity. From the beginning, the Church understood itself as something fundamentally different from the power structures of the world, not a religious version of them.

For that reason, the Church of Christ cannot be identified with systems that monetize grace. It cannot be reduced to an organization that sells access to spiritual acts, whether those transactions are described as fees, stipends, donations, or offerings. Language does not change substance. When money becomes functionally attached to prayer, intercession, forgiveness, or remembrance, the boundary Chalcedon drew has already been crossed.

Nor can the Church of Christ be defined by property ownership or institutional power that mirrors secular governance. When clergy become administrators of wealth, managers of assets, or stewards of political influence, the Church ceases to look like a called-out assembly and begins to resemble the very world it was meant to challenge. Chalcedon did not condemn this possibility out of idealism; it condemned it because it understood how easily spiritual authority collapses when it is absorbed into systems of gain.

The Church of Christ is not sustained by transactions, products, or paid mediation. It does not require commercial mechanisms to function, nor does it need to brand, market, or monetize the name of Christ in order to survive. What was freely received was meant to be freely given. When the name of Christ becomes a source of revenue, the danger is not only moral but theological, because it redefines what the Church is and how it operates.

According to Chalcedon’s own standards, spiritual authority is forfeited when it is bought, sold, monetized, or administered as worldly business. This is not a modern judgment imposed on the past; it is the past judging the future. What emerged historically may call itself “the Church,” may preserve structures, titles, and continuity, but by the criteria it once declared binding, legitimacy is measured by fidelity, not survival.

The uncomfortable implication is that the Church of Christ cannot be equated with any institution that profits from his name. The Church is not a marketplace, not a corporation, and not a property holder. It is a people. And wherever believers gather in faithfulness to Christ without monetizing what he gave freely, there the ekklesia still exists; regardless of whether it owns anything at all.

How, exactly, is purchasing a Mass card supposed to help anyone?

What is the claim being made? That money changes the effectiveness of prayer? That a prayer spoken by a man who claims to be “holy” carries more weight if it is paid for? That God listens more attentively when an envelope changes hands? Or that grace, while officially denied as a commodity, somehow becomes more accessible when it is monetized?

Strip the language away and this is what remains: a religious service is offered, money is exchanged, and a spiritual benefit is implied. It does not matter whether the word used is “donation,” “stipend,” or “offering.” The structure is transactional. And once prayer is placed inside a transaction, it is no longer prayer in the sense Christ taught. It is a service.

What, precisely, is holy about selling one’s prayers?

If prayer is communion with God, then it cannot be priced without being corrupted. If prayer is effective because God hears, then money is irrelevant. And if prayer becomes effective because it is mediated by a paid intermediary, then Christ’s teaching about access to the Father has already been abandoned. The New Testament knows nothing of purchased intercession. It knows nothing of spiritual acts that become more potent when administered by a professional class for a fee.

The defense usually offered is that the money supports the Church or funds charity. But this evades the real issue. Charity does not justify corruption of form. Feeding the poor does not sanctify the sale of spiritual acts any more than laundering stolen money makes theft righteous. The question is not what the money is later used for; the question is what the practice itself teaches people to believe about God.

And what it teaches is this: that access to spiritual care is mediated by money, that holiness can be outsourced, and that prayer can be delegated to those with institutional authority; for a price.

This is not a small distortion. It is a reversal of the gospel.

Christ did not say, “Pay, and it will be given to you.” He did not say, “Seek out the authorized professional.” He did not say, “Those with means will be heard more clearly.” He said, “When you pray, go into your room, shut the door, and pray to your Father who is in secret.” He placed prayer firmly outside public transaction, outside performance, and outside mediation for profit.

So what does a Mass card actually do?

It does not increase love. It does not increase mercy. It does not change God. What it does is soothe anxiety by shifting responsibility. It reassures the buyer that something has been done, that the obligation has been met, that spiritual concern has been properly outsourced. It replaces personal faith, prayer, and trust with a receipt.

And this is precisely why Chalcedon matters.

The council did not merely condemn simony in theory. It condemned the logic behind it: the idea that spiritual authority can be bought, sold, or administered as worldly business. It declared grace unsaleable because it understood that once grace is treated as a service, the Church ceases to be the ekklesia and becomes a marketplace.

You cannot sell prayer without teaching people that God is approached through money. You cannot sell spiritual acts without turning ministers into vendors. You cannot normalize transactions around grace without emptying grace of its meaning.

No amount of charitable output fixes that contradiction.

The Church of Christ is not a service provider. It is not sustained by fees, products, or paid mediation. It is a body of believers who pray because they believe, who give because they love, and who serve because they are called; not because they are compensated.

When prayer is sold, Christ’s name is used as currency.When spiritual acts are priced, grace is no longer grace. And when an institution depends on these practices to function, it has already answered the question of what it truly trusts.

Not God — but money.

Mass cards for the dead rest on a claim that collapses under even minimal scrutiny. They imply that money can secure spiritual benefit for someone who can no longer act, pray, repent, or choose; that a paid ritual performed by an authorized intermediary can improve the standing of a soul before God. This is not faith; it is spiritual outsourcing. It teaches the living that responsibility can be transferred, that grief can be resolved by payment, and that God’s mercy is mediated through a financial exchange. Nothing in Scripture supports this. Prayer for the dead is never commercialized, never delegated for a fee, and never presented as more effective when performed by a professional class. A Mass card does not change the dead; it conditions the living to believe that grace can be purchased. And once grief becomes a revenue stream, the Church has crossed from compassion into commerce, turning the fear of loss into profit and replacing trust in God with a transaction.

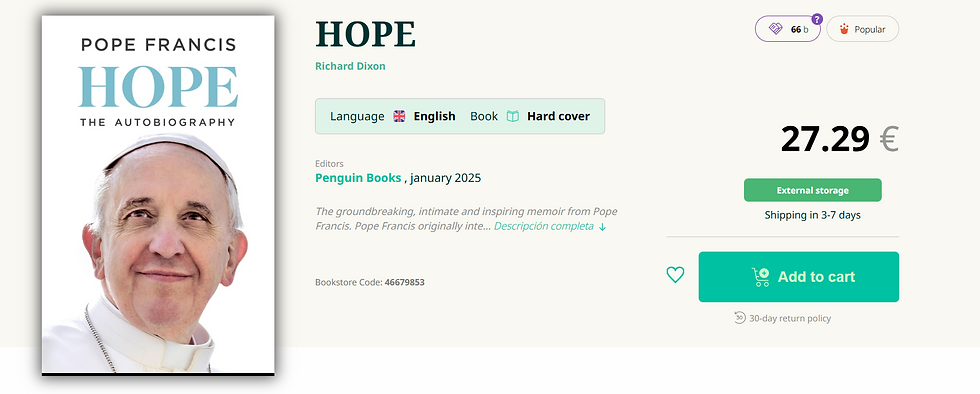

There is something profoundly tragic about a world in which people will eagerly pay for books written by men declared “infallible,” while ignoring the one book given freely by the Spirit of God himself. Shelves fill with papal memoirs, theological reflections, sanctioned interpretations, and authorized explanations; all sold, marketed, and promoted; yet the Scriptures, which claim divine origin rather than institutional approval, remain unopened, unread, or treated as insufficient on their own.

What is being implied by this exchange? That Christ speaks more clearly through men who hold office than through the Spirit he promised to all believers? That private insights allegedly granted to ordained elites carry greater authority than the words Christ openly gave to the world? Apostolic succession that contradicts Chalcedon is succession in name only, stripped of the fidelity that alone gives it meaning. And yet their words are sold, their opinions published, their authority monetized; while the voice of God is treated as something that requires interpretation, permission, or supplementation.

This inversion should trouble anyone who takes the gospel seriously. Christ did not charge for access to his teaching. The apostles did not copyright revelation. The Spirit was not promised to an institution, but poured out on all flesh. Yet here we are, watching the name of Christ used to sell products, the claim of authority used to justify profit, and spiritual credibility leveraged for revenue.

If we return to Chalcedon honestly, the question becomes unavoidable. Should men who use ecclesiastical authority to generate personal or institutional wealth have remained in office at all? Chalcedon explicitly condemned clergy who turned ministry into worldly administration and declared grace unsaleable. It did not carve out exceptions for publishing deals, intellectual property, or religious branding. It did not say, “unless the money supports the institution.” It said such behavior forfeits legitimacy.

By Chalcedon’s own standard, using the Church as a platform for monetary gain; whether through selling offices, selling rituals, or selling words clothed in divine authority; is grounds for removal, not admiration. The council assumed that once spiritual authority is used as a means of profit, it ceases to function as spiritual authority at all.

What makes this especially sorrowful is not merely the conduct of those in power, but the willingness of people to accept it. To trust paid voices over the freely given Word. To purchase interpretation instead of seeking the Spirit. To believe that holiness can be packaged, printed, and sold by men who claim authority yet point away from the simplicity of Christ.

Chalcedon did not imagine this future kindly. It warned against it. And if its judgments are taken seriously, then much of what is now treated as normal should never have been allowed to stand.

Peter warned about this exact corruption long before councils, long before empires, long before publishing houses and religious marketplaces. He did not speak vaguely. He named it.

“And through covetousness shall they with feigned words make merchandise of you.”

— 2 Peter 2:3

Peter is not describing pagans or outsiders. He is warning believers about those who would arise from within, cloaked in religious language, using crafted speech, spiritual authority, and holy appearance to turn faith into a commodity and people into customers. The danger is not crude theft; it is persuasion. Feigned words. Carefully shaped language. The appearance of truth without its substance.

What does it mean to “make merchandise” of people? It means to treat souls as a means of gain. To use fear, grief, reverence, or trust as leverage. To monetize access to God while insisting, outwardly, that grace is free. It means selling reassurance, selling interpretation, selling authority; all while claiming divine sanction.

Peter’s warning fits our age with frightening precision. Books sold under claims of spiritual authority. Mass cards sold to soothe fear for the dead. Films sold in the name of Christ. Objects, rituals, and interpretations packaged and priced. All of it wrapped in religious language, all of it defended as harmless, all of it justified by appeals to tradition or charity.

And yet Peter’s verdict is already given. When spiritual language is used to generate profit, people are no longer being shepherded; they are being merchandised.

This is why Chalcedon matters. It did not invent a new concern; it enforced Peter’s warning. Grace is unsaleable. Authority cannot be bought. Ministry cannot become a business without forfeiting its legitimacy. The council assumed what Peter declared: once gain enters the equation, truth is no longer being served.

The tragedy is not only that such practices exist. The tragedy is that they are accepted. That people trust paid voices more than the freely given Word. That they purchase reassurance instead of seeking God. That they believe holiness can be mediated by men who profit from their authority.

Peter did not say this would be obvious. He said it would be persuasive. Feigned words. And he said it would not end well.

If his warning is true; and Chalcedon assumed it was; then the issue before us is not taste or preference. It is discernment. Because where Christ is freely given, no price is attached. And where people are made into merchandise, the voice speaking is not his.

Comments